320 pages, 25cm x 33cm

2018, Chartwell

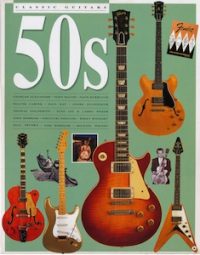

Electric Guitars: The Illustrated Encyclopedia

A massive job, this one. It’s an encyclopedia that covers … wait a minute while I count … 130 brands of electric guitars, from Acoustic (yes, this book on electric guitars starts with the Acoustic brand) to Zemaitis. Major brands get the full treatment, of course, with quite a few at some length, while the smaller brands are necessarily shorter.

To see a list of all the brands covered in the book, click the link here.

We published the original edition – see its jacket below here – back in 2000. In 2018, we revised and updated the book for a new edition, published by Chartwell, and that’s the jacket you can see on the left.

Just now, as I opened my original copy of the book to count the number of brands inside, an old press release floated out. It has some further mind-numbing statistics that I know you’ll want to hear: 320 pages, over 1,200 photographs, including 750 classic and rare instruments and 450 players, original ads, and memorabilia. There’s also a 12-page bit at the front rounding up the pre-history of the guitar before anyone thought about plugging it in.

That press release goes on to say: “Arranged as a comprehensive and informative A-to-Z of guitar brands, written by the world’s leading authorities on the subject.”

Those “leading authorities” … that means me and a trio of hard-pressed helpers: Dave Burrluck, Paul Day, and Michael Wright. We did well, actually. It’s a big book overflowing with informative and entertaining stuff, and I’m proud of it. As the great Paddy McAloon of Prefab Sprout put it in his song of the same name: “Grander than castles, cathedrals, or stars – Electric Guitars!”

176 pages, 21.5cm x 28cm

2016, Backbeat

The Bass Book

As a one-time bass player, I’d always wanted to produce a book that told the story of the electric bass guitar. I’d known Barry Moorhouse for some time, and his fantastic Bass Centre store was based at the time in Docklands, east London. He was the obvious person to hook up with on this one: Barry is a lovely bloke, and he knows everyone. We had a lot of fun making this book.

The first edition appeared in 1995, and the jacket was in the style of our existing guitar books (pictured below left), and then a second edition came out in 2008 (jacket below right) in our larger, softback format.

The icing on the cake came when Paul McCartney agreed to be interviewed for the book. I believe Mr McCartney got out of the right side of the bed the morning my fax arrived asking for an interview. I remain very grateful for his bedroom arrangements.

Click here to read an extract from the interview with Paul McCartney.

Suffice to say, Barry and I were proud to be the first to tell the story of the introduction and development of the electric bass in a book dedicated to the subject.

There’s an interview here that Bass Musician magazine did with Barry and me about the book.

160 pages, 21.5cm x 28cm

2012, Backbeat

Squier Electrics

I wanted to write about this sub-Fender brand not only because it was a great story in its own right, revealing much about how Fender dealt with various kinds of competition through the years, but also because it provided an opportunity to look closely at the sometimes mysterious world of the Japanese guitar industry.

Watch a promo video for the book here. Well, actually it’s me yakking about the book for a few minutes, over which someone has stuck some pictures of the book content.

In 1982, Fender revived an old guitar-string name for its new line of Japanese-made electric guitars. Today, Squier is almost as important to the company as the main Fender brand. I dug up stories behind the original and collectable Japanese-made Squier Series models, the ways in which Fender has often been more adventurous and experimental with Squier, away from its protected main brand, and the famous musicians who chose to play Squier instruments, from Courtney Love and her Venus model to Bollywood’s Ehsaan Noorani and his signature Stratocaster.

Click on the link here to read an extract from an interview I did for the book with John 5.

144 pages, 21.5cm x 28cm

2011, Backbeat

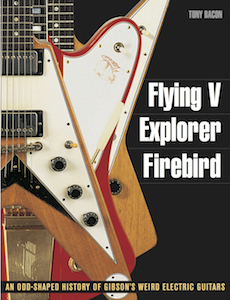

Flying V, Explorer, Firebird

I must admit the title of this one has always seemed a bit clunky. But what else to call it? Those three models are the star of the book, of course, but there’s plenty more here. Until the launch of the V and the Explorer in ’58, electric guitars were supposed to look like … guitars. Suddenly, Gibson turned conventional design on its head, using straight lines and angular body shapes.

In the process, Gibson changed the way electrics could look, and that’s the main story here. I tell the story of the original commercial failure of the V and Explorer, Gibson’s later attempt at a similar style with the Firebird, and then the subsequent influence of these designs on makers such as Hamer, Jackson, Dean, Ibanez, B.C. Rich, and ESP, who all in their different ways endorsed Gibson’s original take on the idea of weird-is-good.

I also spoke to a good number of players to get their view from the land of weird, and the book features exclusive interviews with Andy Powell, Rick Nielsen, KK Downing, Billy Gibbons, Gus G., Michael Schenker, Phil Manzanera, Johnny Winter, Alexi Laiho, and others.

You can read a short extract from my interview with Rick Nielsen if you click on the link here.

If it’s pointy and it has strings, you’ll have a good chance of finding it in Flying V, Explorer, Firebird.

192 pages, 21.5cm x 28cm

2007, Backbeat

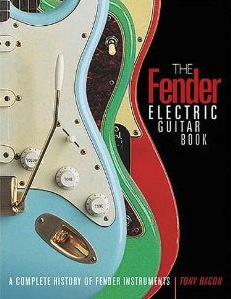

The Fender Electric Guitar Book

This was our complete reworking in 2007 of The Fender Book. We made it in the new format for our Profiles series of guitar-history books, which we’d begun with 50 Years Of The Gibson Les Paul in 2002. It meant a bigger page size and an elegant softback jacket with flaps (for a rare view of the jacket, click here). That in turn meant that we redesigned the picture pages from scratch, and I took the opportunity to rewrite and update quite a bit of the general text as well as to update the reference section.

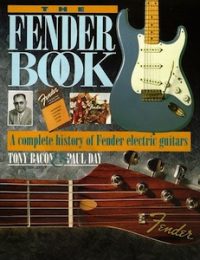

The Fender Book, the book on which this was based, was the very first thing that I published with Nigel Osborne for our new firm, Balafon. We set up Balafon in 1992, in the wake of producing The Ultimate Guitar Book for Dorling Kindersley. (As big fans of abbrev, we always call that book UGB, and its publisher we always called DK, among other things. More on the UGB here.) Balafon later morphed into Backbeat.

Nigel and I always thought of the move to do our own stuff as something like a band making an album for a major label, soon becoming dissatisfied, and then thinking, hmm, why don’t we do this ourselves? And then setting up an indie. Sort of mad and sort of brave. Balafon was our own indie books label (“imprint” in publishing jargon), and it was the start of what turned into Backbeat.

We knew from the success of UGB that people really liked our idea of guitar books with quality writing and quality pictures. Now, don’t get me wrong: that dissatisfaction I mentioned wasn’t with the UGB itself. On the contrary: we were proud of it. It was DK we weren’t so happy with: they didn’t think like we did. We had something else in mind, but retaining all the quality we’d put into the UGB. The result was TFB.

The Fender Book set the template for what we’ve come to call our Profiles series of books – effectively all our illustrated guitar-history books – which as you’ll see from the Books page here is now pretty long and impressive. Back then, however, we were finding our way. Anyway, I wrote the main story, based on lots of research and the many interviews I did with Fender people old and new.

You can read an extract from my interview with Fender boss Don Randall by clicking here.

Paul Day and I painstakingly constructed the reference section that detailed all the Fender electric models, old and new. We sent off photographers Matthew Chattle, Garth Blore, Nigel Bradley, and Will Taylor to snap a load of lovely guitars. Nigel Osborne and Sally Stockwell worked hard on the design for the book. All in all, it was great fun … and it quickly became a success. Here’s the jacket of that original book:

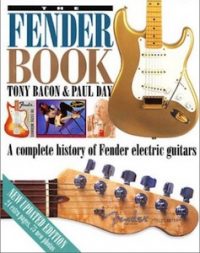

Six years later, in 1998, we published a revised and updated edition, with a new white laminated jacket that you can see in the picture here:

In 2000, we made a sort of side order, 50 Years Of Fender (jacket below left), that ran alongside The Fender Book. For this, Nigel and Sally came up with a completely different look: a double-page spread for each year, starting in 1950, with a featured instrument and catalogues, pictures, and other illustrations on the right, and a story on the left. Rather nice, actually, and this book also added in Fender acoustics, basses, amps, and the rest. In fact, we liked the idea so much, we updated it in 2010 to produce (can you guess the title?) 60 Years Of Fender.

Anyway, back to the timeline for The Fender Book. For the next big update, in 2007, we retitled it as The Fender Electric Guitar Book – and that takes us neatly back to the subject of this entry here, with the jacket pictured up on the left. The Fender Electric Guitar Book remains my current general history of Fender.

88 pages, 25cm x 31cm

2001, Backbeat

Echo And Twang

Echo And Twang, which appeared in 2001, was a re-titled and new-jacketed edition of Classic Guitars Of The 50s (original jacket below) which we’d put out five years earlier. Otherwise it was exactly the same. We did the same thing with Fuzz And Feedback which was dragged distorting and screaming from Classic Guitars Of The 60s (more about that one here).

The idea was to combine a magazine-like editorial approach with the high-quality illustrative look we’d already established.

I rounded up good writers on the guitar and briefed them each on a 50s-related chapter to write for the book. I snagged a good team: Dave Burrluck on guitar construction; André Duchossoir on Gibson; Charles Alexander on jazz; Walter Carter on Fender; Tommy Goldsmith on country; Tom Wheeler on American guitars; Rikky Rooksby on rock’n’roll; Hiroyuki Noguchi on Japanese guitars; Michael Wright on mail-order guitars and on radio and television; Paul Trynka on blues; Stan Jay and Larry Wexer on collectability; John Morrish on recording; and Paul Day on European guitars.

I wrote an introduction to it all, which you can read by clicking on the link here.

Everyone did a great job, and it seemed to me that the result was just as I’d intended: a multi-angled view of the guitar in the 50s, its importance in various styles of music, and all the great and not-so-great players and instruments that helped to create that music.

I’m still particularly proud of this one and its companion, Fuzz And Feedback, because there’s never really been anything like them. I think they were a good combination of my magazine experience and Nigel Osborne’s design experience (although it was Sally Stockwell who actually put the look together).

John 5 Interview

Here’s an extract from my interview with John 5, which I did during the research for the Squier Electrics book.

TB: How did you decide what you wanted for your Squier signature guitar? You play with a range of artists and certainly a lot of styles – which seems to baffle some people. To me, it seems like the obvious thing to aim for – why play the same thing your whole life? I wondered what that means you need from your guitars. Versatility, I guess, is pretty high on the list.

J5: I always thought that the Telecaster, as our first solidbody electric guitar, was the greatest guitar in the world. They should just stop making any other kind of guitar and just make the Telecaster. That’s how strongly I felt about it.

TB: I think that’s what Leo thought, actually.

J5: It’s the best guitar, and it’s a workingman’s guitar. You can’t fake it on a Telecaster. Of course, a lot of people have said that.

TB: It’s true – that’s why a lot of people have said it.

J5: You cannot fake on it a Tele. I was like: nobody in heavy heavy rock ever plays a Telecaster. I was: what is the problem with these people? These are the greatest guitars ever. So me and Alex Perez and Chris Fleming and Mike Eldred [at Fender], we designed my Telecaster. I was like: I want this to be able to scream through the loudest amps, and be able to play like country with it and jazz with it, have it be an all-around guitar. The Les Pauls, they can do that, but they can’t really get that twang, they can’t get that thing, but they can have that heavy type of sound. I really think my Tele can do that and – it’s not because of me, and I’m not taking credit for this at all – but I see a lot more heavy artist playing Telecasters.

TB: Who are you thinking of?

J5: Well, after I started doing it, I saw Jim Root from Slipknot playing one, and I think I saw Tom Morello playing my signature model with his new band, Street Sweeper Social Club. There’s a lot of people playing Teles now. I’m so proud of it, and not just cos it’s such a great guitar – it’s like one of my kids, the Telecaster in general, this is the best, you know? I’m passionate about it.

TB: I like your three-pickup signature model, the Fender J5 Triple Tele Deluxe, too.

J5: It’s great, and that evolved by taking from the three-pickup Les Paul, the Custom. It looks amazing, too, there’s so much chrome on it, and it sounds amazing. In the studio, everything I’ve recorded is always with the Telecaster. You double a lot of tracks with different guitars – but I just double them with different Telecasters.

TB: Do you know how many you have?

J5: I’m close to having a Tele from every year, starting from the Broadcaster. I’m missing a Nocaster, but I have my eye on one. They go up to like 1980. But they’re all amazing condition. And I have multiples from each year, like the 78, 79, all the International Colors, the Antiguas, the Thinlines, in mahogany, all that stuff.

TB: Did you have to go through many prototypes for your signature model?

J5: It worked out pretty quickly because the people over in Corona [at the Fender factory] are just amazing. They’re monsters.

TB: Have you used the signature guitars on record? Do you need to?

J5: Oh, I always do, of course I do. I used it on my instrumental album that’s coming out soon, I used the Squier for doubling on it. I’m not sure of the title yet, no, but I think it’s going to be God Told Me To.

TB: I really liked ‘Bella Kiss’ on your Devil Knows My Name album. It sounded something like an electric John Fahey to me.

J5: And all Teles!

From Tony Bacon’s interview with John 5, May 24 2011

Fender Electric Guitar Book Jacket Panorama

Here’s a view of the jacket you’ll never quite get from The Fender Electric Guitar Book itself: this is the proof copy of the jacket in all its widescreen glory.

Don Randall Interview

Here’s an extract from an interview I did with Don Randall in 1992 during my research for The Fender Book. Don met Leo Fender in the 40s when he worked for Radio Tel, a local radio-parts distributor, and he soon became an important part of the Fender setup. In shorthand, Leo was the introvert designer and Don was the extrovert salesman. It was more complicated than that, of course, but for now, let’s hear from Don.

TB: Who came up with the names for the Fender guitar models?

DR: No one ever speaks about this, but I named every instrument that was made, apart from the Precision Bass. Every one of them. All the amplifiers and all the guitars.

TB: How did you come up with the names?

DR: It wasn’t easy. I tried to maintain a family reference. For instance, we had the Broadcaster, we put it on the market, then we got a wire from the Fred Gretsch company, and they were making a drum set called the Broadkaster. They put us on a notice to cease and desist, which we did. I got to thinking, well, what do we do now? So broadcast … about that time, television was getting big, so telecast, Telecaster. And then when the Stratocaster came along, why, Telecaster, Stratocaster into the stratosphere. With amplifiers we had a student amplifier, and nobody really wants to be known as a student, so I named it the Champ. Then we had another we called the Princeton, and the Deluxe and the Harvard.

TB: What happened with the Precision Bass?

DR: When Leo came out with the bass, it had frets on it, a new type of thing. He was saying oh, Don, it’s right down to hundredths of an inch, a guy plays this he’s going to be perfect. What are we going to call it? I fiddled around with it and I couldn’t come up with anything, so Leo says why don’t we call it the Precision Bass? Because it really is precision. OK Leo, there you go: the Precision Bass. But I must have written out lists of names, 25 names at a crack, trying to fit things together as a family. Doesn’t sound like a chore, but it is: to find something that has a euphonic sound, that is acceptable, that kind of fits into the family of what you’re doing.

TB: At what point did you realise that Fender was going to be successful?

DR: In 1953, when we formed Fender Sales, I was sick and tired of the radio business [that I had been in until then]. We were selling products that everybody else was selling, and they were selling them cheaper than we could. You had what we called wagon-jobbers then, who had a truck full of stuff and they’d just stop at a guy’s place and unload it at his front door. It was hard to compete with that sort of thing. I hated the radio business by that time. I’d spent my life in electronics at that point, and I was a communications chief in the army, and I’d done a lot of design work at that time. So come 1953, when I left Radio Tel, it was decided to form this company, Fender Sales. I could see the potential – we were selling something that nobody else had. The world at that time was kind of hungry for goods and services, because of the war years, and our competition was practically nil. Not that the others didn’t have it, but they didn’t have anything to compete with us. Nothing that stood up to our products. So we turned it on and really started moving it, and it went up and up and up.

TB: Was there ever a time when you felt influenced by what other companies were doing?

DR: Oh, I used to eat my heart out. When I was doing all this, I was spending an awful lot of time out in the territory, working with the salesmen, looking at ideas and everything. And every place I looked I’d see Gibson guitars, Gibson amplifiers, other things that we weren’t selling … where does that come from, what do we do? And when they got to see our stuff … that’s all you’d see, Fender guitars and Fender amplifiers. We’d go down to Nashville and show at the country DJ show, in October, and I worked out a deal down there where we had our guitars and amplifiers in practically every store window on the main streets. We worked it into their display theme, because the country DJ thing was a big item. This was probably in the mid 60s.

TB: Did you ever play an instrument?

DR: Well, like I say, I play guitar, but not enough to hurt anyone.

TB: Were many of the people who worked at Fender players?

DR: Very few. Most musicians are more interested in playing and talking than working, and it was rather hard for us who didn’t know enough about the music to get into arguments. The idea when you went to see a dealer was to sell and get out of there, not to get into an argument over whether this is good or that’s good.

From Tony Bacon’s interview with Don Randall, February 18 1992

Echo and Twang Introduction

This is my introduction to our 1996 book Classic Guitars Of The 50s (which we published again a little later with a new title, Echo And Twang).

The 50s created the teenager; the teenager demanded pop music; and pop music’s shiniest icon was the electric guitar. This book magnifies the links in that chain, and will plug you in to a decade of astonishing contrasts, blinding invention, and great, great music.

The world was changing rapidly in the 50s. World War II had ground to a bloody halt in 1945. It had shaken some countries to bits, reduced others to bankruptcy, given renewed confidence to a lucky few. Despite the ruins and the indelible marks of suffering, as the 40s gave way to the 50s, people were determined to enjoy themselves at last, to celebrate their survival and continuing existence. One obvious way was through music.

Sex was popular, too. “The abnormally high birth rate since 1940,” said a US financial report of 1950, “has continued through 1949 and has resulted in about 33 million births, which soon will have an important influence on school facilities, on housing, and on food requirements.” And, more crucially perhaps, on new trends in leisure and entertainment. “The great social revolution of the last 15 years,” wrote Colin MacInnes in 1958, “[may be] the one that’s given teenagers economic power … for let’s not forget their ‘spending money’ does not go on traditional necessities, but on the kinds of luxuries that modify the social pattern.”

The stage was set for change: many kids who grew up in the war were tougher and more independent than those who had gone before. They were ready for anything – and they wanted more. The new teenagers of the 50s – only later would they be called baby boomers – were greater in numbers than ever before compared to the overall population. Crucially, they had money in their pockets and a new-found freedom in which to spend it, more or less as they chose. A survey of American teenagers’ spending habits in 1958 revealed that they represented a buying power of no less than $9 billion. And, more often than not, at the top of their wish list was the latest rock’n’roll record.

Businessmen were not slow to appreciate the link between music listening and music making. The Harmony guitar company, for example, teamed up with Decca Records in 1955 for their Dance-O-Rama promotion where, as they described it, “Guitar players will be inspired to buy records and record fans will be encouraged to buy the instrument they like to hear.”

Not only did the 50s host the birth of rock’n’roll, but the new music led inevitably to a concentration on the guitar as one of the prime instruments at the heart of this musical revolution, aimed at and often created by teenagers (or, at least, by teenagers at heart). The United States was the site of this revolutionary melting pot, and the newly created mixtures were whisked rapidly around the world.

And yet these were far from idyllic times. Always close to the headlines in the 50s was the potential peril inherent in atomic or nuclear power. It seemed only a matter of time before someone would lift the lid of this Pandora’s box and finish everyone off for good. The threat of The Bomb was omnipresent – maybe it could resolve the Korean War, or sort out Suez? After all, it had finished a much bigger war just years earlier. Nuclear fallout shelters sprang up as a rather inappropriate defence. And in the quickly developing climate of the cold war, no-one in the West had much doubt as to who would be hurling the bombs at them.

Reactions to the Communist Threat of the dastardly Russians ranged from the typically unimaginative politician (Harry Truman: “Our lives, our nation, all the things we believe in, are in great danger, and this danger has been created by the rulers of the Soviet Union”) to the more subtle innuendo of the movie house, where the sci-fi-Shakespeare of Forbidden Planet starred an unstoppable terror that roamed a doomed world, killing everyone.

As if all this wasn’t enough, you just couldn’t trust anyone – spies were everywhere. No matter: J Edgar Hoover and the FBI would be the protectors of every true US citizen. Spy fever reached its terrifying climax when American couple Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, found guilty of running a nuclear-espionage ring that passed information to the USSR, were executed by electric chair in 1953 – the first Americans ever sentenced to death for spying, in war or peacetime.

For many people living through the period, the 50s were a peculiar mix. There were great leaps being made in science and technology, some of which were distant and hard to grasp, like rockets blasting into space, while others such as transistor radios or stereo records were closer to home and easy to appreciate. But underpinning all the innovation was a general unease, a feeling that the world was an unruly place that was spinning out of control. As Jack Kerouac, founder of the so-called Beat Generation, had one of the characters say in On The Road: “I had nothing to offer anybody except my own confusion.”

America had the new music, at least for the time being, and so America had the guitars. Meanwhile, Europe had it bad. In Britain, for example, there was one word that came up again and again to describe the mood. Austerity. Post-war austerity. Rationing lasted well into the 50s, bomb sites were everywhere, greyness and gloom prevailed, and thanks to a cash-strapped government the importing of musical instruments and gramophone records “from the dollar areas” was banned from 1951 to 1959. Rock’n’roll inventiveness necessarily lagged behind the American model, which was streaking ahead with tailfins glinting. Even politician Harold Macmillan’s famous line, “You’ve never had it so good,” delivered in 1957 when prospects had brightened, was taken from a US election slogan of five years earlier.

Relatively speaking, the United States had finished the 40s without the crippling expense and psychological fallout that so many European countries had suffered as a result of World War II. Of course, there were some financial burdens – and the US musical instrument industry, at least, endured a recession from the late 40s until about 1952. One can tell that there must have been a recession, because the contemporary press was flecked with articles insisting that there was no recession.

In fact, the guitar started the 50s at a disadvantage. A craze for the ukulele had begun at the end of the 40s in the US, where over three million of the irritating little things were sold up to 1953. Fashion hounds everywhere forced their fingers into cramped chord shapes. The lowly ukulele was even elevated in 1950 to the status of an instrument recognised by the musicians’ union in the New York area.

The accordion, too, was on the crest of a popular wave, buoyed up by bandleader and accordionist Lawrence Welk. His proto-MOR ‘champagne music’ was alone enough to make any self-respecting teenager seek musical alternatives. In jazz and early rock’n’roll it was the saxophone that dominated the instrumental frontline, and only in country, blues, and Les Paul’s multi-layered chart hits did the guitar start the decade with any kind of musical stronghold.

But by 1954, the guitar’s fortunes were changing. A report by the American Music Conference in that year, estimating the number of people playing musical instruments in the US, put the guitar at 1.7 million, ukulele at 1.6 million, and accordion at 950,000. The sax was lumped in with ‘others’ at 975,000.

Two years later, the dramatic rise of rock’n’roll underlined the guitar’s versatility and fundamental simplicity, nudging the instrument to a peak of popularity. Charles Rubovits of the Harmony guitar company of Chicago seized on the positive signs when he wrote in a guitar industry report of 1956: “More people have the growing desire to do things themselves rather than be spectators; more people have more leisure time; more people are more easily exposed to music through television, creating a desire for self-expression; and more people have and will have more money to buy the things they want. Desire for fame and fortune is another motivating influence working in our behalf. Although we know the heights are reached by only a few, those attempting to gain this goal are many, proving this sales factor to be a reality.”

Sidney Katz, president of the other big Chicago-based guitar manufacturer, Kay, told a trade gathering a few years later to overlook their own musical prejudices and chase the teenagers’ dollars. “No matter how you feel about rock’n’roll and Elvis Presley,” he said, “for business they have been great, and guitar sales have been rising steadily as a result. People are getting tired of sitting in front of a television set; they want to get together and entertain themselves – and there’s no better instrument than a guitar for building a convivial atmosphere,” Katz concluded. No doubt he had stressed exactly what his audience of businessmen wanted to hear: that big guitar sales would bring the American family closer together, singing wholesome songs together around the hearth. None of that rock’n’roll rubbish, that’s for sure.

Reactions among parents and the establishment of the 50s to Elvis and his brand of guitar-based jungle music ranged from the outraged to the morally indignant. “Rock’n’roll is the most brutal, ugly, vicious form of expression,” Frank Sinatra told the New York Post in 1957, describing it colourfully as “the martial music of every delinquent on the face of the earth”. A vicar in England told the Daily Mirror that the effect of rock’n’roll on youngsters was “to turn them into devil worshippers; to stimulate self-expression through sex; to provoke lawlessness, impair nervous stability, and destroy the sanctity of marriage.” With that kind of manifesto, most teenagers merely wanted to know where to sign up.

Musical snobbery was rife, too. Steve Race, a British big-band pianist – and Light Music Advisor to the ATV television company – wrote in Melody Maker in 1956: “After Presley, just about anything can happen. Intonation, tone, intelligibility, musicianship, taste, subtlety – even the decent limits of guitar amplification – no longer matter. I fear for the future of a music industry which allows itself to cater for one demented age-group, to the exclusion of the masses who still want to hear a tuneful song, tunefully sung.” It’s a pity that Race didn’t copyright that last bit, because it’s been used ever since by every generation who can’t help but criticise their kids’ worthless music.

Jazzmen of the 50s, too, were horrified by the inept noise and artless rhythms of the new music. Leading jazz guitarist Barney Kessel, used to his modestly amplified hollowbody electric guitar, but as a sessionman necessarily responsive to new sonic requirements, told a reporter in 1956: “I had to buy a special ‘ultra toppy’ guitar to get that horrible electric guitar sound that the cowboys and the rock’n’rollers want.” And that same year a writer to the letters page in the jazz musician’s chief magazine, Down Beat, was clearly affronted. “The epitome of this musical suicide is reached by persons of the ilk of Elvis Presley, who seems to have a talent for sneering, jumping up and down, crossing his legs, standing on his head, playing down to his audience – in fact, a talent for everything but music. What makes it worse is the fact that this guy is making out so well while more talented and deserving artists pick up the crumbs.”

During the pages that follow, we’ll analyse the decade’s guitars and place them in the context of the music of the time. The guitars themselves, photographed to reveal every detail, provide the chronological order of the book, while around and about them a team of the world’s top guitar writers bring their expertise to bear on the key elements in the story of the guitar-laden 50s.

We see Chet Atkins at work on his pop-country hybrid and Les Paul constructing his New Sound, widening the popularity and appeal of the electric guitar; we marvel at Tal Farlow pushing and reshaping the boundaries of jazz guitar playing; we hear the low-down twang of Duane Eddy’s hit records; watch Scotty Moore at work with Elvis Presley, and Frank Beecher behind Bill Haley; we investigate everything from the black R&B of Chuck Berry to the white pop of Buddy Holly; and we examine Stratocasters and Explorers, Duo-Trons and Byrdlands, Emperors and Clubs and Switchmasters. Classic Guitars Of The 50s for the first time explains how the electric guitar grew up and established itself during ten mesmerising years. This book tells it like it was.