HENRY DILTZ: LIFE THROUGH A LENS

It was in 1979 that Henry Diltz experienced the true power of an amplified guitar in a big venue. He’d been hired as the photographer for a tour by The New Barbarians, Ronnie Wood’s shortlived solo supergroup with Keith Richards on guitar, Bobby Keys on saxophone, Stanley Clarke on bass, Ziggy Modeliste on drums, and Ian McLagan on keys.

“We got on the private plane,” Henry says, speaking by phone today from his house in the Hollywood Hills. “We flew to a city, got in the limos, went to the hotel. I’m hanging out with them, taking a few pictures and stuff.”

Next afternoon, they found themselves at the initial venue, in Toronto, and it’s soundcheck time. “The first music I heard was Keith, way up on stage—I was out in the back of the empty auditorium—and he played one chord on his guitar: worangggg! It completely filled the room. It was like when a bass drum passes in a parade and that boom, boom hits you in the chest. It was like an avalanche. And I thought to myself that one chord just says Rolling Stones. It was so loud, yet so warm—and not annoyingly loud, because it kind of went inside of you. And oh my god, it just blew my mind.”

Back in 1966, Henry had been in his late twenties when he first picked up a camera. Before that, he was the banjo player in the Modern Folk Quartet, and he had plenty of musical friends in and around Los Angeles. That first camera was a cheap Japanese model he’d come across in a secondhand shop, and soon he moved on to a better Pentax. He enjoyed putting on slideshows to show his transparencies at parties, and the response was good.

Gradually he was becoming A Photographer, although his recollection is that he didn’t particularly consider himself as such, and that he got into it by accident. “It’s not a job, and I don’t feel like I’m even a photographer,” he reckons. “People would see me with a camera and say, ‘Oh, you’re a photographer—are you a professional?’ I’d say no, not really—and this was even when my pictures started to turn into album covers. You English have the phrase ‘up the front’, and when you’ve got a camera at a gig, you get to go up the front. My Chinese zodiac animal is a tiger, and tigers like to hide in the bushes, get close to other animals, and watch them, observe them. That’s what I feel like I’m doing. I’m just watching and waiting for the right picture, you know?”

Every moment can be a picture, he says. “If you’re on tour with a group, and say you’re in the dressing room, you want to be judicious. If you’re just snapping at everything, it’s going to be annoying. I like the art of framing. That’s the point for me.”

We talk about one of Henry’s most famous pictures-that-became-an-album-cover. Crosby Stills & Nash hadn’t been together long when Henry got a call in 1969 to shoot some publicity pictures for the new trio. “They were making their first album and they hadn’t had any pictures taken. They were just thrilled to be singing together—they’d come over to somebody’s house and sing ‘Blackbird’ in three-part harmony. It was so freakin’ beautiful that everybody would fall down. But they didn’t have any pictures to even say these guys are now singing together. So we spent the day driving around West Hollywood.”

Graham Nash had earmarked an abandoned house, and there out front was an old couch. “They plopped down on it,” Henry says, “and this was a great example of the importance of framing I mentioned. A couch is a rectangular piece of furniture, you get the edge of the couch on each side of the frame, their heads go right to the top of the frame, and their feet are on the bottom. It frames horizontally just so tightly and perfectly. But we weren’t shooting a cover, we were shooting publicity photos. Or at least that’s what the mission was. But my partner in these things, the graphic artist Gary Burden, saw the possibility of a cover there. Very often it’s kind of an accident. The accidental album cover!”

Henry was snapping away, and that frame of three guys on a couch he describes is what most people would call to mind if they think of the front cover of CS&N’s first album. And, of course, we would peer closer at Steve Stills’s rather nice-looking Martin. “But Gary would always say to me: ‘Back up, back up!’ And in this case: ‘Get the whole house!’ I’d back up, and back up, and he’d be: ‘Back up some more!’ Well, I ended up across the street,” he recalls, still amused by the memory. “And even though the cover is the tightly framed shot of them on that couch, it wraps around to the back and you see a door and a chair there to the left.”

A similar thing happened to one of Henry’s shoots that ended up supplying the cover for the following year’s Doors album Morrison Hotel. “I was up close shooting kind of sideways, down the window, and the four of them were looking up at me,” Henry recalls. “It was a funny shot, and again Gary said to me, ‘Back up, back up! Get the whole window!’ And once again I went all the way across the street. I always like to move in and frame tightly. He always saw the big picture. And he was right. It taught me—he was my teacher—that it’s good to also get a nice wide shot and show what else is going on.”

There’s a photograph from the ’79 Ronnie Wood tour that shows the value of a wide shot and Henry’s ability to leap from the metaphorical bushes to capture a moment. “There are like eight limousines pulled up around the airplane after we touch down,” he says. “We walk down the steps, and everyone starts looking for their limo. The road manager’s saying: ‘OK Woody, you’re over here with Keith, Bobby in that one over there… .’ Keith Richards is walking through it all, and I turn around, have a real wide-angle lens on, and just snap a picture on the fly.”

He didn’t take much notice of it when he went though the shots later. “And you know what? That’s one of the only pictures of mine that ever got cropped. On the proof sheet, there’s a whole lot of space on the left, and a lot of sky above Keith. It sat on that proof sheet for years and years, until about 2010, when an artist wanted to do some artistic posters with my photos. I said OK, but not the iconic ones—you have to find ones on the proof sheets I’ve never used. He went straight to that one! So we cropped it in from the left and from the top, and I had to admit it looked great. And to this day, that’s one of our best-selling photos at the Morrison Hotel Gallery, which I started some years ago with friends.”

You’ll find hundreds of classic shots at the Gallery—morrisonhotelgallery.com—from Joni Mitchell to Jerry Garcia, The Monkees to the Eagles, Lou Reed to Bruce Springsteen, and much in between. One that Henry counts among his personal favourites is another almost casually captured photograph that would end up on an album cover.

Peter Asher had been one half of the pop duo Peter & Gordon, but by 1969 he was managing and producing James Taylor. “Peter called me one day, asked if I could come over and shoot some black-and-white publicity photos of this guy at a friend’s place where they had some interesting barns and outbuildings.”

As they wandered around the site, James stopped to lean on a post. By now, Henry was using a pair of Nikons, usually one loaded with black-and-white film and one with colour, to replace his Pentax cameras that had proved less than robust for a working photographer. And once again, the tiger was watching and waiting, looking for his moment and his framing. “James had an elbow out and he was leaning on this post, with an arm up,” Henry says. “His arms perfectly filled the horizontal frame from elbow to elbow. It was such a great photo, right there.”

He told James not to move. “I shot black-and-white, and then I picked up my colour camera, thinking I’ve got to get a colour slide of this to show my friends in the slideshows, even though Peter wanted the black-and-whites. Well, they saw that colour picture and it became the cover. I like that photo a lot, though not that cover. Inside the original record was a double-album-size pullout, 12 by 24 inches, and it was that picture, close up, that I really like. You can see the full-frame original of the black-and-white on our website.”

Henry is still at it today, as happy to talk about those halcyon days in the 60s and 70s as he is to discuss the benefits of modern digital photography. He seemed happily unfazed by the coming and going recently of his 83rd birthday. The week before we spoke, he’d been photographing Emmylou Harris at a small charity bash. And he says all his jobs, back in the day or right now, start with a phone call in his kitchen in Laurel Canyon.

Back in the summer of ’69 it was Chip Monck on the blower. Henry knew Chip, a busy lighting guy, from his days on the folk-club circuit. Now Chip was telling Henry about a “huge outdoor concert” coming up, that he ought to be there, and that he’d talk about him to the show’s producer, Michael Lang.

“Next day,” Henry says, “Michael, a man of few words, called me, said: ‘Chip tells me we need you, and I’m sending you $500 and a plane ticket.’ So I went out to the site of the Woodstock festival, a few weeks before it began.” He spent the days photographing a team of hippies happily hammering and sawing the big wooden aircraft-carrier of a deck that became a stage at the bottom of a hill.

“That hillside was filled with green alfalfa blowing in the wind, almost like you were at sea,” Henry remembers. “I’d go over and watch the hog farmers, a commune setting up the camp grounds, smoke a doobie over there, watch them set up teepees, walk around and take photographs, come back to the stage work. Then in the afternoon, the hippie girls from the office would come with sandwiches and drinks and stuff. It was like a blissful summer camp, just Elysium. And when people started filling up that hillside, at first I was thinking, ‘What the hell are they doing here?’ It was almost a surprise when all the action started happening.”

With Woodstock under way, Henry stayed pretty much permanently up on the side of the stage, cameras to hand, watching and waiting as ever. He couldn’t get to his room a mile or so down the road, anyway, what with the blocked roads, so he slept in his station wagon at the back of the stage. He photographed most of the performers, from Richie Havens to The Who, through to the Sunday when the festival was due to finish. But he was woken on Monday morning by an announcement from the stage, and he caught the words “Jimi Hendrix”.

“Wow! I jumped up, grabbed my cameras, ran up the back stairs, and got there just in time to photograph Jimi from 20 feet away. And then he played ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’. It was such a surprise. We were the peace-and-love hippies, we were against the Vietnam war, and against the government sending people over there. So for a second, you thought wait a minute, that’s their song. What is he playing that for? And then the next second you think, wait, he’s claiming it back. That’s our song. And then he put all those sounds in, neuuurrrr, bap-bap-bap-bap-bap, like airplanes diving and bombs going off and machine guns. Nobody will ever make a guitar talk like Jimi Hendrix could.”

Much of the audience had gone home by the time of Jimi’s early-morning performance. “It was just a cluster of people by then, and the hillside of green alfalfa was now just mud,” he remembers, “and cow manure, and the mixture of people having been there for three days. There was a huge smell! When the sound from the speakers went out and bounced against those empty hills, and came back like an echo in the air, it was kind of eerie. That field looked like a battlefield, like those old pictures of the Civil War where you’d see dead horses and dead soldiers. There were soggy sleeping bags and broken tents, things that people had left right in the middle, spread over that hillside. And then Jimi playing that amazing piece of music amidst it all.”

The tiger was ready. “I like to see stuff happening, I like people,” Henry says. “I never went to photo school. So I smoke god’s herb and I use god’s light,” he adds, with yet more laughter.

“To me, it’s all about looking through the lens, framing things up, enjoying the visual, and then pushing the button when it looks optimal, when it’s exciting. I’m not a technical guy. I know what I need to know. I never developed a roll of film in my life. It’s all about that moment! Like Jimi, right there, playing ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’. And like Keith playing that one warm, loud chord that filled your soul. It’s just that moment. Bang! Get that! And you keep doing that.”

By Rick Landers, posted at Guitar International in 2011

Any guitarist who has walked the aisles of the nearest Barnes & Noble or roamed the guitar related entries at Amazon.com has seen the name Tony Bacon. For the past couple of decades Tony has been linked to well-researched tomes on Gibsons, Fenders, Gretsches, and thousands of pages about cool, historic, unique and downright weird guitars.

Digging in deep to offer readers accurate and interesting information on the world’s most famous and obscure guitars is not an easy road. One must pore over old magazines, interview guitar industry experts, get some quality time with top celebrity guitarists, then check and double-check every fact, and then present the material that’s grammatically correct, aesthetically pleasing, and presentable in a form to successfully meet the market. It’s damn hard work, but at the end of the day must be very satisfying, and Tony Bacon by all accounts should be delighted.

Our office at Guitar International carries a load of Tony’s books that serve as reference books, as well as recreational retreats when we need a break from guitars to, well, our favorite pastime – guitars. So, we decided to talk to Tony about writing books, guitars, the entry of ebooks to the publishing arena, as well as his search for the world’s most valuable guitar.

Rick Landers: Getting started as a writer these days is pretty easy, in a time when nearly anyone can start a website and start writing. But, when you began your career, publishing outlets were not only limited but very competitive. Tell us about the challenges and the strategies you used in order to get your books in print and how that’s changed over the years.

Tony Bacon: My first book was Rock Hardware, published back in 1981, but my first dedicated guitar book, and one that I think many of your readers will know, was The Ultimate Guitar Book, published in 1991. Nigel Osborne and I produced the book for Dorling Kindersley, a big general-book publisher. The success of that made us consider the situation in a way that many musicians at the time were thinking about record companies: Why should we do books for a big publisher when we could do it ourselves?

So Nigel and I set up Balafon and started producing our own books, distributed in the US through Miller Freeman, who then published Guitar Player and other magazines. Our first four titles were The Fender Book (1992), The Gibson Les Paul Book (1993), The Rickenbacker Book (1994), and The Bass Book (1995). I think that with these early ones we created a new kind of guitar book.

I came to book publishing from journalism, while Nigel was already designing and creating books. I think it was that professional experience and attitude, combined with a passion for guitars, which made our books different. Today, as you say, anyone can “publish” their ideas and views on the net. That’s a wonderful development that has some positive impact on us all. But, on the other hand, a lot of what you see on the net is opinionated and not researched. Everyone’s an expert.

My favorite question to pose when someone offers some theory as fact is this: “How do you know that?” If the answer is along the lines of “Oh, I just know … ” then I know it’s safe to ignore it. Our values at Backbeat UK and Jawbone of accuracy and attention to detail still count for a lot, I think – and perhaps even more these days.

Rick: What steered you toward writing non-fiction, rather than writing novels or creative short stories?

Tony: As I say, my background was professional journalism. I worked for a number of British musical-instrument magazines in the 70s and 80s, so I knew how to write about technical subjects in an engaging and entertaining way.

I was aware of some of the “new journalism” trends at that time, where writers like Tom Wolfe and others used some of the techniques of fiction writing in their non-fiction work, and I like that approach. I used it to some extent in my 2008 book Million Dollar Les Paul, for example.

Rick: How did you begin writing something like The Ultimate Guitar Book?

Tony: The UGB was a mammoth job of organization, and every book I’ve worked on subsequently has involved the same kind of careful, painstaking approach. Our guitar books generally combine three broad areas: the main story, the pictures, and the reference section.

For the central part of the book, the main story, I start with an outline, and then add in detail as I research, interview and learn. An important thing to remember is that you must always be open to finding out new things and not have a fixed idea of how you think the story ought to be.

When I first started writing, we used these strange objects called typewriters, but of course it’s much easier today to work piecemeal on your text, adding and expanding and editing as you go. The pictures are another area where we worked hard to get things right, and I think we introduced to guitar books the idea of high-quality commissioned photography.

We’ve used some great photographers, like Miki Slingsby, and I’ve spent a lot of time over the years tracking down owners and persuading them to have their guitars featured in our books. What’s not to like about showing off your pride and joy in this way?

Anyway, the last part is the reference section – what we call the trainspotter’s guide – and that’s usually researched by Paul Day or Walter Carter. We create a scheme designed to be helpful and useable for identifying and finding out about all the models covered by each book. Again, we try to solve the questions that we think readers will want answered, rather than going off on our own tangents. Generally, we aim for our books to be well written, properly researched, and attractively designed, and to combine factual knowledge with an enjoyable vibe.

Rick: It seems pretty obvious that you must be a guitar player, right? What or who got you interested in playing music, rather than just being a listener?

Tony: I got the bug when I was about 15 – a long time ago – and began playing bass in various bands. Nothing famous or well known, but a hugely enjoyable time. Soon after that I got interested in writing, and it became obvious that I was going to be a much better writer than a guitarist.

Rick: What’s the toughest phase of writing a book, the beginning where you have to first put pencil to paper or the final phase making sure everything’s “perfect” and ready for your readers?

Tony: You have to stay alert all the way through. For me, I find that it’s sometimes hardest between the early stages of ‘got the idea’ and ‘OK, go and do it’. It can seem sometimes that you’re circling the idea and forever putting off starting. It’s remarkable the number of excuses you can find to not begin writing! But once you’re in and running, there’s nothing better.

One of the bits I like best about putting together my guitar books is tracking down and interviewing people to help me tell the story. For my recent book Rickenbacker Electric 12-String: The Story Of The Guitars, The Music, And The Great Players I managed to get to more or less everyone I wanted: Peter Buck, Roger McGuinn, Tom Petty and Mike Campbell, Johnny Marr, Dave Gregory, Mike Pender, and many others. It makes such a difference.

Rick: What about keeping your books up to date? Do you find that it’s necessary to revise earlier versions or are they locked down as published the first time? If you revise your older work, is that a drudgery to have to revisit something you considered done and complete?

Tony: We do revise and update the books regularly, and it’s so satisfying to be able to do that. Again, a music parallel: how often do you get to remix something? How often would you like to tweak a little there, add a touch of this or that here? Nearly all my guitar books cover the current story as well as the past history, so there are always new developments to take care of, too.

Rick: You’ve written with some major focus on Gibsons and Fenders, so I’d guess that those tend to be your favorite guitars, but what others do you find particularly suited to your playing?

Tony: I have three guitars. I know: people usually expect me to have some vast collection. But I’ve seen and played some of the most amazing guitars in the world, and if I indulged myself at every opportunity I’d be destitute.

I don’t have the collecting bug. Well, correction: I do collect catalogues and pictures and info … but not guitars. I like to mess around on my beat-up old Yamaha acoustic—although I really ought to get around to fixing that dodgy bridge.

And I have a couple of 60s Euro guitars featured in the UGB, purely as “lookers:” a Hopf Saturn 63 and a Bartolini pushbutton-crazy concoction. I strongly identify with the remark that the late Don Randall, sales boss at Fender in the classic years, made once when I asked him if he played guitar. “Not so it would hurt anyone.” Exactly.

Rick: There have been some very intriguing guitar designs over the years, Gittlers, the Strawberry Alarm Clock Mosrites, and the artful guitars by Ulrich Teuffel, along with others. Have you dug into that arena or do you prefer the more traditional guitars to write about and play?

Tony: I love all kinds of guitars. I don’t care one little bit about whether I’m “supposed” to like this or that model or revere this or that period. As someone once said about music, there are only two types. What you like and what you don’t like.

Rick: Many new writers are exploring the world of eBooks in order to gain more traction in building their own profit margins, rather than rely on what I understand are relatively small percent royalties typically handed out by print publications. Are you seeing a dramatic shift from print to ebooks as a way to sell and distribute books? Your thoughts on the pros and cons of this medium?

Tony: In the book trade, ebooks are currently the big unknown. Everyone thinks they are going to be big, but no one knows yet exactly how it’s going to work, whose “reader” will dominate, how authors will benefit, which types of book will prove most suitable, and so on. Again, I’d draw a parallel with how musicians find themselves when technological developments present an apparent opportunity.

Yes, it appears to be easier to get your stuff out there. But how do you make people aware of what you do, how do you present your material in a professional-looking form, and how do you actually sell it? The printed book as we know it is a highly-developed piece of technology that’s been refined over hundreds of years. The ebook is pretty new, so it’s not surprising that its true value hasn’t been established yet. We’re trialing some of the books in our Jawbone line as ebooks and we’re monitoring how that goes.

Rick: A recent book of yours is about your search for “the million dollar Les Paul.” Do you mind giving us a run down on how that search went and, if you found that valuable guitar, has the market shifted downward to make it no longer worth a million bucks?

Tony: I really enjoyed writing Million Dollar Les Paul: In Search Of The Most Valuable Guitar In The World. The idea was to find out why the Bursts – those amazing Les Paul Standards from 1958–60 – have become some of the most expensive and hallowed guitars on the planet. I looked into the history, the construction, the famous players, the collectors, the reissues, the whole close-knit industry that has built up around these guitars.

And I dug a little deeper into questions like why people collect, how we put values on objects, and why we like to play what our favorite players use. It was a fascinating journey, and I don’t think it would spoil things to say that I didn’t actually find a million-dollar Burst. Or at least one that anyone would admit to. It’s my favorite book of all those I’ve written. The Los Angeles Times called it “a romantic quest for a guitar whose craftsmanship borders on the mythic,” which seems about right.

Rick: Given the books you’ve written about Les Paul guitars, did you ever meet the legendary player behind the name on those headstocks?

Tony: I did meet Les Paul, several times over the years, and Les was always friendly and helpful to me, for which I’m grateful. I enjoyed the way he would always be right there in any story about musical history you cared to throw at him, and I would smile at the way his stories would develop and grow over the years I knew him – but most of all, I Ioved the way he played. He interviewed the way he played, too: humorously, engagingly, and unquestionably the center of attention. I’ll miss him.

Rick: There are hundreds of guitar builders around the world now, but Les Pauls, Stratocasters, and Telecasters still capture the imagination of both new and older guitarists. Are we all just a bunch of conservative traditionalists or is there something magical about those guitars?

Tony: It’s a bit of both. There is magic in the classic designs, for sure. That’s why we call them classics. It’s not an exaggeration to say that guitarists, as a tribe, are pretty conservative. That’s why Gibson has so much trouble getting players to take to its various digital guitars, it’s why Fender dropped its modeling Strat after a short time on the market, and it’s why you don’t see too many other radical remakes about. Those classic designs work, and they work well. Why redesign the wheel?

Rick: With Les Paul and Leo Fender now gone, what builders are out on the market now that will be considered the milestone builders in twenty years?

Tony: I don’t know that and nor does anyone else, whatever they might tell you. We’ll find out in 2030. I hope.

Rick: With vintage values set aside or in a “blind test”, which guitars are going to outperform the others, the ‘50s vintage guitars or the one’s built today?

Tony: It would be good to think that with all the benefits of modern production, with all the leaps in understanding, that the ones built today would surely win. It would also be good to think that all the acres of print written about the special magic of a vintage guitar actually added up to something tangible. I wonder how much of all this is because we can’t ignore the backstory when we pick up something we know is XX years old (and, incidentally, worth YYYY dollars)?

There’s a psychology at work there, of course. If you pick up a 2010 Stratocaster, you should be able to play and feel and sound just as good as you do on a 1956 Strat. But never underestimate the power of your imagination. Vintage-guitar dealers certainly don’t.

Ultimately – and sorry if this seems like a cop out, and sorry to repeat a cliché – but it all depends on the way you, or I, or anyone else reacts to a given guitar. I like this one; you like that one. I think this neck is the most comfortable I’ve ever held; you prefer that one. I reckon this pickup tone is heaven; you run screaming in the other direction. Beauty will always reside in the hands and ears of the beholder.

Rick: Do you have any new writing projects underway that you’ll tell our readers about?

Tony: There’s always something new; that’s one of the things I like about doing this. I wear two hats, really: I write books, and I publish books. I co-own two publishing imprints, Backbeat UK and Jawbone. At Backbeat UK, we devise and produce books for Hal Leonard’s Backbeat imprint, and these include all the guitar books that we’re talking about here, as well as books about songwriting, playing instruments, technical guitar stuff, and so on.

At Jawbone, our own imprint, we publish what we call ‘reading’ books about music and musicians. Personally, my latest book, for Backbeat, is The Stratocaster Guitar Book: A Complete History Of Fender Stratocaster Guitars, and I’m currently working on a new one about Flying Vs, Explorers, Firebirds, and their pointy progeny. Our latest batch of new Jawbone titles includes Becoming Elektra: The True Story Of Jac Holzman’s Visionary Record Label by Mick Houghton. So it’s never dull around here.

Rick: Let’s finish up with one of those stupid “what if” questions – just for fun – You get a chance to meet and get a personal guitar lesson from a top Telecaster player, a Top Les Paul player and a Top Stratocaster player – Who are you going to choose for each? (The players can be dead or alive).

Tony: Let’s see – this sort of thing tends to change depending on what day you ask me and what I’ve been listening to – but right at this moment it would have to be Peter Green on Les Paul, Jeff Beck on Strat, and Albert Lee on Tele. Oh, I’ve just noticed those are all Brits. Can I cheat and have another three Americans? Just to balance the books? Yes? OK, let’s add my today’s-faves: Neil Young on Les Paul, Bonnie Raitt on Strat, and Denny Dias on Tele. Actually, mention of the fabulous Mr. Dias has got me itching to hear Countdown To Ecstasy. I should go … .

This is an extract from my interview with Ken Parker for my book Electric Guitars: Design & Invention. These days, Ken is back to making great acoustic archtops, but our chat centred on his design for the Parker Fly electrics first seen in the early 90s.

TB: The headstock design of the Fly was one of its important elements, I think.

KP: OK, let’s go back to Turkey, whenever it was, a thousand years ago. They were building uds, or the precursor to an ud, and because they didn’t have Monster cables and amplifiers, they had to do everything they could to get the thing to bark and speak so it was useable. And one of the things that you need to do is to reduce the weight of the vibrating object so that you can accelerate it with the very small amount of energy that you have in a little bitty string. If you can’t accelerate it, then it’s not gonna move any air, and nobody’ll buy it. So these things were built very lightly, and if you look at their heads, they’re tiny, as small as they can get. You look at a lute, the pegbox is this little arts & crafts project, where a million little pieces of thin wood are stuck together, just barely enough to hold the tuning pegs.

TB: What’s the reason for that?

KP: Weight is completely unwanted in that area. Also, when a guitar player or bassist puts their hand on the neck, whether they’re sitting or standing with the instrument, you’ve just made a gigantic modification in the physical attributes of that instrument. You with your boney bag of protoplasm that we call a hand, you have just colossally modified the structure. And every time you move your hand, you reconfigure that modification in a very important way. The influence of this bag of protoplasm with bones in it is gonna change where the nodes of vibration are on the neck. Everybody that I know talks about instruments as if they’re on a stand somewhere, or in some anechoic chamber; nobody says we lean over them, fat people envelop them, skinny people don’t, lightweight people and kids have little hands, giant men have giant hands … these are huge differences.

TB: How do you allow for that, though? Because there are so many differences and potential changes.

KP: I would submit that the guitar is possibly the most complex design project in instrument making. And I know people are gonna laugh and say what about a harpsichord. Yes, but a harpsichord, you only want it to do a certain kind of music, nobody’s doing hip-hop on a harpsichord.

TB: Let me make a note to get my harpsichord hip-hop project going.

KP: Yeah, ha ha. You have a certain repertoire you’re gonna play. If you have a guitar, you can play anything. So many different ways of playing a guitar. It’s what makes it so viable. In furniture – I used to make furniture – in furniture making there is nothing as hard to build as a chair. For the same reason. You’re gonna have a little kid sit in it, and the next person might weigh 350 pounds, and they’re gonna sit in it and lean back. People with different length limbs and torsos: it’s just really complicated. It makes designing a dresser look really simple. Or a dining room table. But the chair is really a bitch. In the world of instrument making, I submit that guitar design is really a bitch.

TB: The guitar is the chair of the instrument world.

KP: Yeah, exactly. So if you go to a good trade show for hand builders, like the Holy Grail show or something like that, you’ll see so many different approaches to solving these problems, to try and address the guitar to meet the needs of whoever. If you’re copying an L-5, well, you’re in no danger of having a shred guy fall in love with you. But to me it’s always seemed really important to build the most versatile instrument that you could build, so that people could do anything they want with it.

TB: That was part of the Fly. Even aside from the design and intention of that instrument, one of the most significant things about it was that it was aimed to be mainstream, and to me that’s one of the most interesting things about it. Looking back now, that’s why it was such an important instrument in the history of the guitar.

KP: Well thanks. I didn’t really think about it that much until I did the ’14 and ’15 Holy Grail shows, and I had a lot of builders come up to me and say: Your work sat me on my ass and gave me the inspiration to know that I could scratch my head and change things and it was OK. And I just loved that. I don’t have any letters, people didn’t write me … well, maybe a couple of letters. But mostly you don’t hear that stuff. It just happened over and over again in this group, and I thought wow, that’s … how great is that, you know?

Here’s a list of all the brands covered in Electric Guitars: The Illustrated Encyclopedia. Major brands get the full treatment, at some length; smaller brands are necessarily shorter.

A Acoustic; Airline; alamo; Alembic; Alvarez; Ampeg; Aria.

B Baldwin; Bartolini; BC rich; Bigsby; Bond; Brian Moore; Burns.

C Carvin; Casio; Chandler; Charvel; Coral; Custom Kraft.

D Danelectro; D’Angelico; D’Aquisto; Dean; De Armond; Domino; Dwight.

E Eggle; Egmond; Eko; Electar; Electra; Electro; Epiphone; ESP.

F Fender; Fenton-Weill; Fernandes; Framus; Futurama.

G G&L; Gibson; Gittler; Godin; Godwin; Gordon-Smith; Goya; Gretsch; Grimshaw; Guild; Guyatone.

H / I / J Hagstrom; Hallmark; Hamer; Harmony; Harvey Thomas; Hayman; Heartfield; Heritage; Hofner; Hondo; Hopf; Hoyer; Ibanez; Jackson; James Tyler; John Birch.

K / L Kapa; Kawai; Kay; Kent; Klein; Klira; Kramer; Krundaal; LaBaye.

M / N / O Magnatone; Martin; Maton; Melobar; Messenger; Micro-Frets; Mighty Mite; Modulus; Mosrite; Music Man; National; Ovation.

P Parker; Peavey; Premier; PRS.

R Rickenbacker; Rick Turner; Robin; Roger; Roland.

S Samick; Schecter; SD Curlee; Shergold; Silvertone; Spector; Squier; Standel; Starfield; Steinberger; Stratosphere; Supro.

T Teisco; Teuffel; Tokai; Tom Anderson; Travis Bean.

V Vacarro; Valley Arts; Vega; Veillette-Citron; Veleno; Vigier; Vox.

W / Y / Z Wandre; Washburn; Watkins; Welson; Westone; Wurlitzer; Yamaha; Zemaitis.

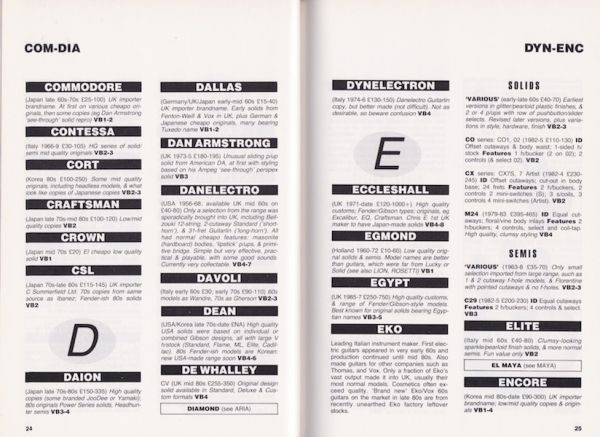

Here’s a sample two-page spread (pages 24 and 25) from the first edition of The Guru’s Guitar Guide, and then below that is a list of all the brands included. As you can see from the sample, some of the entries are very brief indeed; the Eko entry here is one of the longer ones. As I said elsewhere here, don’t expect a fancy production, great pictures, or detailed text. This is hard info for guitar nutters only.

Brands in the Guru’s Guide:

A Alembic; Alligator; Ampeg; Angelica; Antoria; Applause; Arbiter; Aria; Arirang; Aristone; Asama; Audition; Auroc; Avon; Axe; Axeman; Axis; Azumi.

B Baldwin; Baleani; Bambu; BC Rich; Bert Weedon; Besson; Blade; Blundell; BM; Bond; Boogaloo; Bozo; Broadway; Burns.

C Cairnes; Celebrity; Chandler; Charvel; Charvette; Chris Larkin; Cimar; CMI; Colt; Columbus; Commodore; Contessa; Cort; Cradftsman; Crown; CSL.

D Daion; Dallas; Dan Armstrong; Danelectro; Davoli; Dean; De Whalley; Dynelectron.

E Eccleshall; Egmond; Egypt; Eko; Elite; Encore; Epiphone; Eros; ESP; Europa; Excetro.

F Fender; Fenix; Febnton-Weill; Fernandes; Fingerbone; Firefox; Framus; Franconia; Fresher; Freshman; Frontier; Frontline; Futurama.

G G&L; Galanti; Geoff Gale; Gherson; Gibson; Gilson; Gittler; Godwin; Gordon Smith; Gordy; Graffiti; Grant; Grantson; Grenn; Gretsch; Grimshaw; GTX; Guild; Guyatone.

H / I Hagstrom; Hamer; Harmony; Hawk; Hayman; Heart; Heartfield; Heritage; Hofner; Hohner; Hondo; Hopf; Hoyer; Hurricane; Ibanez; Immage.

J Jackson; Jarrock; Jax; Jaydee; JB Player; Jedson; Jennings; Jerry Bix; JG; JHS; John Birch.

K Kasuga; Kawai; Kay; Kent; Kimbara; Klira; Kramer.

L Lag; Larrivee; Launay King; Levin; Lew Chase; Lincoln; Lion; Lynx.

M Madeira; Manson; Marina; Marlin; Martin; Maton; Maya; Melody; Merlin; Miami; Michael; Michigan; Micro-Frets; Mighty Mite; Mirage; Montana; Moonstone; Morch; Mosrite; Munroe; Music Man; Musima.

N Nadine; Ned Callan; Nerve; Nightingale; Ninja; Northworthy.

O Oakland; Odyssey; Optek; Orange; Ortbit; Ormond; Ovation; Overwater.

P / Q Pack Leader; Palmer; Pangborn; Patrick Eggle; Paul Reed Smith; PC; Pearl; Peavey; Pete Back; Pickard; Profile; Pulse; Quest.

R Raver; Regal; Rickenbacker; Rickmann; Ritz; Riverhead; Robin; Rockson; Roger; Rosetti; Rotosound; Royal.

S Sakai; Sakura; Samick; Sanox; Satellite; Saxon; Schecter; SD Curlee; Seiwa; Selmer; Shadow; Shaftesbury; Sheltone; Shergold; Sierra; Signature; Simms-Watts; Sola-Sound; Spector; Squier; Staccato; Stagg; Star; Starforce; Starway; Status; Steinberger; Sumbro; Sunn; Super Twenty; Sylvan; Synsonics.

T Takeharu; Tanglewood; Teisco; Tempest; Thomas; Tokai; Tom Anderson; Top Twenty; Travis Bean; Turner; Tuxedo.

V Valley Arts; Vantage; Veilette-Citron; Vester; Vigier; Virtuoso; Vision; Vox.

W / X/ Y / Z Watkins; Welson; Westbury; Westone; Wilkes; Wurlitzer; Yamaha; Yamato; Zemaitis; Zenta.

This is the foreword I wrote for the Ultimate Edition of Beatles Gear, a much extended and revised version of the book that appeared in 2015. It’s almost exactly the same as the foreword that appeared in the book itself.

George Harrison told a reporter in 1964: “I started learning to play the guitar when I was 13 on an old Spanish model which my dad picked up for fifty bob. It’s funny how little things can change your whole life.” I know what he means. I probably thought it was just a little thing when I first met Andy Babiuk. It was back in the 90s, and I needed help with a chapter I was writing about Beatles guitars in one of my books. We got on well and revelled in a common love of all things Beatle, but especially the instruments the group used. Just how did they get that fantastic sound?

Andy told me about the ambitious project he’d started, a book that would cover the entire story of the guitars, drums, amps, keyboards, and anything else the group had strummed, hit, plugged into, blown, or otherwise got a sound from during their brief but illustrious career. My small firm ended up publishing Andy’s big book, and in 2001 it appeared at last: the first edition of Beatles Gear.

Andy had put together something remarkable. What I particularly liked about his approach was that, as a working musician, he was realistic about how The Beatles had dealt with the gear available to them. He was enough of a fan to want to know all the intimate details, but he was clear-sighted enough to know that what really happened was often an oddball mixture of chance, opportunity, and happenstance. Andy has a real knack for finding the stories behind the stories, and he won’t necessarily go along with the accepted “truth” just because that’s what’s always been said about such-and-such a Beatle instrument and how it came to be played on a particular record or tour. We published the book; we were all very proud; soon it became a hit. Now it’s time to remake and remodel.

I once rather cheekily asked George Martin if, on reflection, there was anything he’d change on the Sgt Pepper album. Ever the gentleman, he paused to think. “I would put a much longer gap between the end of ‘She’s Leaving Home’ and ‘Kite’,” he told me. “I think it needs more space. It’s such a poignant song, and that jars a bit. I thought it was hip at the time – so there we are. Another thing: listening on CD, I hear the hiss of the records that were used to dub in the sound effects on ‘Good Morning’. They were taken off discs. You didn’t notice it too much on the vinyl but, my god, you notice it on the CD! Sorry about that, folks.”

If it’s OK for George Martin to even consider redoing a small part of something like Sgt Pepper, then I’m entirely comfortable with what we’ve done to Beatles Gear. I do hope you enjoy this new surround-sound version of the book and all the bonus material. Have a splendid time!

This is the favourite-60s-tracks playlist from the Fuzz & Feedback book. I had each of the writers (self included) choose a couple of tracks to illustrate guitar in the period. This is what we came up with – and you’ll notice they’re more or less in chronological order.

To hear these as a playlist at Spotify, click here.

The Flee-Rekkers ‘Sunday Date’

single A-side 1960

Dave ‘Tex’ Cameron (guitar unknown)

* Otherwise British, the group were led by Dutch-born musician Peter Fleerackers. ‘Sunday Date’ was typical of many UK early-1960s guitar instrumentals to achieve fleeting fame – this one with the benefit of a Joe Meek production. For me the record’s important not so much for its unsurprising guitar playing, but because it recalls the frustration of listening to interference-ridden Radio Luxembourg, the main provider of pop music in Britain at the time. Paul Day

Howlin’ Wolf ‘Spoonful’

single A-side 1960

Freddy King and Hubert Sumlin (twin lead, probably both on Gibson Les Paul gold-tops)

* This Willie Dixon-penned mystery story is supercharged by the twin guitar talents of Freddy King and Hubert Sumlin, and can be classified both as primitive artefact and state-of-the-art pop song. One hundred and sixty thrilling seconds document the collision of ancient black culture and the electrified modern world. But what the hell do the lyrics mean? Paul Trynka

Wes Montgomery ‘Gone With The Wind’

from The Incredible Jazz Guitar Of Wes Montgomery LP 1960

Wes Montgomery (probably on Gibson L-5CES)

* Building his ideas over several choruses, Wes unfolds a solo of sustained inventiveness and technical accomplishment. Flowing effortlessly from single-line improvisation into an extended octave passage, he draws things to a perfect conclusion with a spectacular chordal solo. Fresh melodic motifs constantly appear, to be re-shaped and sent on their way, while rhythmic counterpoints pile on the pressure, before relaxing back into straight swing. A true jazz masterpiece. Charles Alexander

The Shadows ‘Apache’

single A-side 1960

Hank B Marvin (lead, on Fender Stratocaster), plus Bruce Welch

* The record that launched 10,000 bands in Britain. Hank made it all look so easy, with those stark, clever melodies wrapped in that super-clean sound. And when the man in the music store looked down his nose at you and said, “What sort of electric guitar do you want, then, sonny?” the reply was obvious: “A red one, like Hank’s, please sir.” Well, something like Hank’s, anyway. But definitely red. Tony Bacon

Jørgen Ingmann ‘Apache’

single A-side 1961

Jørgen Ingmann (probably on Gibson Les Paul gold-top)

* Reworking the ‘New Sound’ that Les Paul invented in the late 1940s, a new breed of guitarists set the tempo of the 1960s with US hits like The Ventures’ ‘Walk – Don’t Run’ in 1960 and Swedish guitarist Jørgen Ingmann’s self-produced ‘Apache’ the following year. Ingmann’s record uses multitracking combined with echo effects, bluesy bends, muted double-picking and harmonics over a rock beat – and it all sounded great in the garage. Michael Wright

The Ventures ‘Lullaby Of The Leaves’

single A-side 1961

Bob Bogle (lead, on Fender Stratocaster) with Don Wilson

* ‘Lullaby Of The Leaves’ blasts out of the chute with a ‘Walk – Don’t Run’ style intro and then kicks into an ascending melody that’s topped off with a radical (for the time) whammy dip. It was one of the first hit instrumentals in which the whammy was integral to the melody, and it also features a driving bass/guitar/drums unison 16th-note chorus. Tom Wheeler

Booker T & The MGs ‘Green Onions’

single A-side 1962

Steve Cropper (on Fender Telecaster)

* Steve Cropper’s stinging, string-torturing licks hit so hard that he only needed to launch them in the sparsest of clusters. In F, of all keys, and at the tender age of 20, Cropper wielded his stock Telecaster to devastating effect in this classic R&B instrumental. Tommy Goldsmith

If one extreme of 1960s guitar was prolix, effects-laden and overdriven, the other was bright, tight-lipped and burnished. Memphis mofo Steve Cropper here delivered the ultimate in lean, mean and clean: elegant, understated Telecaster classicism that didn’t waste a single pickstroke. By comparison, Clint Eastwood was a hysterical blabbermouth. Charles Shaar Murray

Lonnie Mack ‘Memphis’

single A-side 1963

Lonnie Mack (probably on Flying V)

* Lonnie Mack’s 1963 smash instrumental version of Chuck Berry’s ‘Memphis’ was a milestone. It took the intensity of 1950s guitarslingers like Berry, Link Wray, Duane Eddy and Bo Diddley, and upped the stakes with an astonishing fuel-injected mix of speed, articulation, fluidity, and a spine-tingling jolt of Bigsby-vibrato prowess. The virtuoso instrumental rock guitarist had arrived. Tom Wheeler

The Beach Boys ‘Fun, Fun, Fun’

single A-side 1964

Carl Wilson (on Fender, probably a Jaguar)

* I’m not sure I’d even heard of Chuck Berry when I first heard this record, but the arresting 17-second intro, borrowed from Berry’s ‘Back In The USA’, has always epitomised rock’n’roll guitar to me. Carl Wilson was 17 at the time. He’s been plagued ever since by people wanting reassurance that yes, he really did play it. John Morrish

Wes Montgomery ‘West Coast Blues’

from Movin’ Wes LP 1964

Wes Montgomery (probably on Gibson L5-CES)

* Purists tend to consider Montgomery’s Riverside recordings as his best, but I remember being more thrilled then by Verve LPs like Movin’ Wes or Smokin’ At The Half Note. The power and the swing that emanate from this shorter version of his most popular composition is incredible – and his rendition of ‘Caravan’ on the same LP is well worth a listen, too. André Duchossoir

Roy Orbison ‘Oh Pretty Woman’

single A-side 1964

Jerry Kennedy (lead, on Gibson ES-335), plus Wayne Moss and Billy Sanford

* The signature lick is everything – melody, rhythm, chord structure and, most important, attitude. Orbison wrote the lick but on the session he played rhythm on a Gibson acoustic 12-string. The record was a line of demarcation, ending an era of thin, lyrical lead guitar styles and establishing the new, aggressive, in-your-face style that led to ‘Satisfaction’, ‘Day Tripper’ and all that followed. Walter Carter

The Remo Four ‘Peter Gunn’

single B-side 1964

Colin Manley (possibly on Fender Jazzmaster)

* This was an impressive British all-guitar version of Duane Eddy’s hit, with the sax lead lines accurately re-created by Manley (“He makes most other British guitarists sound old-fashioned” said George Harrsion in 1964). Keith Moon-style manic drumming contributed to an over-the-top performance which made me realise that guitar playing shouldn’t be taken too seriously. Paul Day

The Ventures ‘Slaughter On Tenth Avenue’

single A-side 1964

Nokie Edwards (lead, on Mosrite Ventures), plus Don Wilson

* For me this is the best example of the playing of Nokie Edwards on a Ventures track, and I much prefer this to The Shadows’ version. Originally bassist with the group, Edwards had swapped instrumental roles with guitarist Bob Bogle in 1963. There is a wonderful sound to Edwards’ guitar on this track, where almost every guitar technique is included. This is how I was taught that lead guitar should be played. Hiroyuki Noguchi

The Beatles ‘Ticket To Ride’

single A-side 1965

Paul McCartney (lead, on Epiphone Casino), plus George Harrison, John Lennon

* The one record that occupies the cusp of beatboom and psychedelia. Behind it lies the optimistic pop of Berry and Holly. In front of it stretches a brave, frightening new world. Three guitars and a drum kit make up an almost symphonic soundstage, while the distorted guitars and drugs references are rendered even more potent by being held firmly in check. Paul Trynka

The Beatles ‘And Your Bird Can Sing’

from Revolver LP 1966

George Harrison (lead, on Gibson SG Standard), plus John Lennon or Paul McCartney

* Someone once called this “the best guitar playing you ever heard” and I’d be hard put to disagree. George, along with harmonies by John or Paul (memories differ), provides an ultra-bright, 16th-note rampage as intro, backing and riveting solo for the proto-hippie tune. As well as Revolver, check out the Anthology 2 version for a more Byrds-influenced take, complete with Rick 12-string. Tommy Goldsmith

* In my view, the combination of George Harrison and John Lennon is one of the best in the whole of 1960s guitar playing, and on this track you can hear elaborate guitar licks and an emotional harmony at work. Listen too for the way in which the twin guitar phrasing is deployed with such a mastery of melody. Hiroyuki Noguchi

The Beatles ‘Taxman’

from Revolver LP 1966

Paul McCartney (lead, on Epiphone Casino), plus George Harrison

* Even now, ‘Taxman’ comes as a shock, not so much for its non-1960s sentiments as for the coruscating strangeness of the guitar solo. With its vaguely sitar-ish descending runs, and self-contained air, this seemed a product of George Harrison’s Indian obsession. Now we know it was Paul McCartney all along. John Morrish

The Butterfield Blues Band ‘East-West’

from East-West LP 1966

Mike Bloomfield and Elvin Bishop (twin lead: Bloomfield on Gibson Les Paul gold-top or Sunburst; Bishop probably on Gibson ES-335)

* In this sprawling 13-minute instrumental rock raga Bloomfield and Bishop intertwined modal melodies in pulsed crescendos punctuated by Butterfield’s brilliant harp. It’s one of the earliest flings in 1960s pop culture’s emerging affair with eastern philosophy and psychedelia, creating the model for the twin-lead heavy guitar rock that was to follow. Michael Wright

The Yardbirds ‘Shapes Of Things’

single A-side 1966

Jeff Beck (lead, probably on Fender Esquire), plus Chris Dreja

* I was 13 years old, my first guitar still a good nine months into the future. Across the fuzzy ether from Wonderful Radio London came what sounded like an alien marching tune, interrupted by the most demented, far-out musical noise my young ears had heard. Was that a guitar? It must have been – each time it came on I would leap to my feet, hands convulsing Cocker-like in ludicrous imitation of its crazy execution. It was going to be a fantastic year. Dave Gregory

Cream ‘Sunshine Of Your Love’

from Disraeli Gears LP 1967

Eric Clapton (probably on Gibson SG Standard, or Les Paul Sunburst)

* The song and the riff are true classics from the late 1960s and form a timeless vehicle for improvisation. But ‘Sunshine Of Your Love’ also exemplifies Clapton’s typical ‘woman tone’ which many aspiring guitarists were then keen to imitate. And it looked even better when played live and loud on a painted SG Standard. André Duchossoir

Jimi Hendrix Experience ‘Are You Experienced’

from Are You Experienced LP 1967

Jimi Hendrix (on Fender Stratocaster)

* As a mature 14-year-old I’d already learned to play all the songs off From Nowhere… The Troggs . So Jimi’s debut album came as a bit of a shock. After 35 minutes of the music of the gods, Hendrix closed the record with this stunning track, apparently created almost entirely in reverse. It was remarkable that anything musical could be achieved from such a random process, yet here was an emotional, coherent, perfectly-executed solo that, 30 years later, I am unable to turn away from whenever I hear it. Who but Hendrix would have dared attempt such a feat and pull it off so perfectly? Dave Gregory

Jimi Hendrix Experience ‘Little Wing’

from Axis: Bold As Love LP 1968

Jimi Hendrix (on Fender Stratocaster)

* Jimi shows how to take a standard Stratocaster and bend it to one’s own purposes. He exploits the hard, brittle bite of the pickups for the affecting intro, sprinkles the rest of the song with his deceptively fluid meld of lead and rhythm styles, and plunges the trem system into the oh-too-brief closing solo. So that’s what a Strat can do. Tony Bacon

Steppenwolf ‘Magic Carpet Ride’

single A-side 1968

Michael Monarch (lead, on Fender Esquire), plus John Kay

* It’s the rhythm. While most guitarists were concentrating on the blues, Steppenwolf followed the example of the early rockers and took the rhythm element from R&B. They kicked it into overdrive and came up with a crunching rhythm sound so strong that a conventional lead part was unnecessary. Walter Carter

Tony Williams Lifetime ‘Spectrum’

from Emergency LP 1969

John McLaughlin (probably on Gibson Les Paul Custom)

* Tipped from the mid 1960s as a guitarist to watch, McLaughlin confirmed his arrival as a major innovative force with the playing on this track. Its angular theme, crunchy chords, soaring melody and urgent rock rhythms springboard McLaughlin into a blistering solo of Hendrix-like intensity, the fresh harmonic ideas and technical fluency of which announce the agenda for the jazz-rock and fusion music that was to come in the 1970s. Charles Alexander

Jimi Hendrix & Gypsy Sons And Rainbows ‘The Star Spangled Banner’

from Woodstock LP 1970 (recorded August 1969)

Jimi Hendrix (on Fender Stratocaster)

At the dawn of the 1960s, who would have thought that a guitar could sound like this – or, indeed, that anything could sound like this? Or, for that matter, that a guitar could say this? Marshalling (no pun intended) every erg of his powers, Hendrix delivered a complex, wrenching state-of-the-nation address without opening his mouth, or needing to. The Stratocaster said it all. Charles Shaar Murray

This is an extract from my interview with Rick Nielsen for my book Flying V, Explorer, Firebird. Definitely someone to talk to on this subject, as he’s had them all … and I always enjoy chatting to Rick.

TB: When did you first become aware that there was such a guitar as a Gibson Explorer or a Flying V?

RN: Well, I saw pictures, and I’d get all the catalogues and brochures. I had that Gibson catalogue with the original V, the funny double-necks in there – but you never saw people actually playing them. I saw Albert King, he had one way back, and Dave Davies had a Flying V, but that was pretty rare to see any of those kind of instruments around. So I was aware of them.

Then in the late 60s, early 70s, I was aware of the stuff because I was looking for an Explorer but I could never find one. The ones that I did see were usually blues guys, and they probably got a good deal on them, cos nobody was buying them really.

My personality, to this day … I’m never going to look like Jimmy Page or Jeff Beck, a lot of guitar players they dream of being That Guy. I never dreamed of being anybody, ha ha. So the guitars I wanted would go more towards my personality. That was the reason why I had Hamer make that very first Explorer for me, because they weren’t available, but they were cool.

TB: Did you get your hands on a real Explorer before the Hamer?

RN: Right around the same time, I got that one and then I got a real Explorer, and it was all right, it is as cool as I thought. The actual regular Explorers are actually a little bit lighter than the Hamer: they made the Hamer more like a Les Paul. I don’t think Paul Hamer knew anything about korina or anything like that.

TB: The first modernistic Gibson you got was this Explorer?

RN: Yes, still have it.

TB: Can you recall how you got it?

RN: Yeah, I do, I got it from Larry Briggs, had a guitar store in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and he was asking … I think this was ’76 or ’75, ’74, right around there, in that range. Because we’d tour all the time, a week in Oklahoma City, in New Orleans for a week, Miami, North Dakota, just so we could play, and I’d always be scrounging around looking for stuff. Back in those days, if you could find anything like that they weren’t like crazy money. You’re trying to help the poor guy that owns it or the music store: you don’t want to have that crummy old thing, here let me have it.

I had Les Pauls before … like the one I sold to Jeff Beck. I had kind of stuff way before I had Explorers and Vs and stuff like that. Did you know Larry Henrickson, Ax-In-Hand, the collector? I have a sales receipt from Ax-In-Hand. He only wanted the pristine stuff, and he was the highest priced guy back in the late 60s, early 70s. I went down there, I have a receipt I should email you, it’s pretty funny: shows I bought two Stratocasters, maple neck, with cases, and a Firebird, for $200 or something stupid. Because if it was beat up a little bit, he didn’t like it. You could only get the crummier stuff, in his eyes, and it was really a fair price. Try to get one of his sea foam green whatevers, however, and his prices were higher than anybody else. He had all this great stuff in his store, but I don’t think anyone ever bought anything except the beat-ups.

Back to the Explorer with Larry Briggs, I think he was … I also have a price list from George Gruhn, in ’76, original Explorer, hard case, the whole deal, $4,000. I bought that one, too, but I traded stuff for ’em.

This is a short extract from an interview I did with Jimmy Page in 2014. I was so glad to get this interview, one that I’d been seeking for years and years. But it came just too late to include in Sunburst, which was a right pain. Oh well, something for the next edition. In the meantime, here’s a short extract from our chat, which took place at a secret location in west London.

TB: So, you take your Telecaster with you into Zeppelin, and that lasts certainly the first album period, before you get the Les Paul.

JP: Absolutely, the first album is done on the Telecaster, because it is a transition from the Yardbirds to Led Zeppelin, it’s exactly the same guitar. It’s not until 1969 that I get the Les Paul. I’ve already got the Custom. But Joe Walsh insists on sending me this guitar. And it actually looks as though it’s been refinished, looked like it. He bloody insisted, he said you’ve got to buy this guitar! I said I don’t necessarily need it. No, you’ve got to have it, just try it, you’ll want it … and all that. I said I’ve already got the Custom. No, no, you’ve got to try it!

TB: Did you know at the time there was a difference, the Custom and the sunburst?

JP: I knew it was a good guitar. I knew there wouldn’t be the feedback, the squealing you got from the Telecaster, which every night there was a whole episode of controlling that, you know what I mean? Everybody had that if they started turning up a Telecaster loud, you know? So he insisted that I bought it, and I did buy it, and I kicked off the second album with it.

TB: He came to a gig, did he?

JP: Yeah, it was at the Fillmore or Winterland, one or the other, in San Francisco.

TB: Can you remember: he turns up with this guitar …

JP: He turned up, because he used to turn up. I saw Joe Walsh in the days of the Yardbirds, he used to come to the Yardbirds gigs, and then there was the James Gang.

TB: He would have been in the James Gang at that time, I think.

JP: I don’t know … whether he was about to form the James Gang, you’ve got to go quite a way back.

TB: So he turns up with this guitar.

JP: You’ve got to buy this guitar! He kept insisting. I said ah, no, no, no, I can’t afford it. You know how it is. This wasn’t like dealing with Selmer’s here. He was really sporting, he’s still sporting about it now. Because everyone goes oh, you sold him a Les Paul for whatever it is, hundreds of dollars. Oh, it was a pro rata price, he wasn’t stealing me up and he wasn’t giving it to me as a present.

TB: You got a wonderful guitar, though, didn’t you?

JP: You see, it’s the intervention, again, of the guitar. So earlier on, one guitar is left behind at a house, the next guitar, even though I buy the Black Beauty … but then there’s a sort of energy-charged guitar in the Yardbirds that Jeff Beck had …

TB: Which was the one left at the house?

JP: The very first guitar that I had, the camp-fire guitar, was left behind by the people who moved out. You know what I’m talking about, the intervention of the guitar. Then there’s that one, then Joe Walsh insists that I buy this guitar. There’s no guarantee that I would have played the … I don’t know, it’s hypothetical, but I may not have come up with the riff of ‘Whole Lotta Love’ on the Telecaster. That fat sound you’re working with, you are, you are inspired, well I am, and I know other people are, by instruments, the sound of the instruments, and then they’re playing something they haven’t played before, and it’s really user-friendly, and suddenly they’ve got some sort of riff, which is peculiar to that moment. I’m not saying that’s the first thing I played on it, but it was to come.

Here’s an extract from the interview I did for The SG Guitar Book with Tony Iommi. It’s a particularly interesting one because Tony is among a few examples in the book of a player who got sidetracked from actual Gibson SGs and had a custom guitar made.

TB: The “Old Boy” that John Diggins made for you seems to have served you very well.

TI: Oh god yeah, I’ve had a good few many years out of that one, and it really is one of me favourite guitars.

TB: What is it about it? Sometimes everything just comes together.

TI: It does, yeah. To find a guitar that you really feel comfortable with. In fact, funnily enough, Brian May was over here last week, and we were sitting talking about this particular thing, him with his old guitar, and me. It just kind of comes to life in a way, it becomes part of you, you’ve had it that long it becomes aged. I don’t know, I suppose it’s like a violin, the wood ages, and it gets sweeter. It just had that thing, it had got the age to it and it had got the comfortableness to it.

TB: It’s almost like it wears into you.

TI: It does, and again, by playing it, you wear it in and get used to it. When I pick a new guitar up, it’s whoo, really weird.

TB: I think you went back to Gibson quite a bit later, didn’t you?

TI: Yes I did. The reason I left Gibson, quite honestly, in the early days … I say early days, it was round about in the 80s … they sent me three or four guitars. First of all they were right-handed, which I was really pissed off about.

TB: You’d have thought they could get that right. [Tony is famously a left-hander.]

TI: You’d have thought they’d get that right. I looked at the workmanship and it was really crap. I did complain and said I won’t be using them again until they get better. Then later on they sort of approached me about doing my own Gibson. We went through all the stages of it. I liked them.

TB: It must have felt like quite an honour, really.

TI: Yeah, it was really good, I was really proud that they were going to make them for me and have a guitar after my own name – and my pickups, as well, because that’s the first pickups they’d made of somebody. They always had their own pickups, and to have them to use mine for the first time, that was brilliant. I went over to Nashville for a while and we worked in the Gibson factory there, testing them till we came up with the right one.

TB: Mike [Clement, Tony’s tech since 1990] was telling me the pickups on the Old Boy were sealed, and John Birch couldn’t remember exactly what he’d done.

TI: Well, that’s John, he never bloody remembers, ha ha. But what I liked about John as well was he’d experiment, he’d try stuff – you could suggest something and he’ll try it, and it was good.

TB: That’s the good thing about having the guy you go to, rather than a big company.

TI: Exactly, exactly. And that’s what I sort of said, when we went with Gibson, I said I want to be involved in this, I don’t want something plonked up and stick my name on it and that’s it. And the guy we worked with at Gibson, JT Riboloff, was great.